Story by Alexa LaVersa

The names of fish – sardines, mackerel and sole – ring out at Athens Central Market, known as Dimotiki Agora, where kiosks also display a colorful assortment of crustaceans, squid and octopus. Even in the middle of a weekday, crowds bustle through, tourists wandering in with big hats and cameras while Athenians pick over the fillets for that evening’s meal.

On the display tables, wild fish intermingles with fish raised in controlled «farms,» the difference only evident in the price tags penned on placards stuck in the ice. As fish stocks in the Mediterranean continue to dwindle, prompting the Greek government to put limits on how much fishermen can haul in, this sight is becoming more common.

«Fish farming is the highest increasing animal sector, increasing in averages about 6 percent every year,» said Ioannis Karapanagiotidis, a professor of aquatic animal nutrition from the School of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Thessaly in Greece.

They call it «aquaculture,» which means fish kept in huge cages and fed pellets of ground-up grain and other fish unappetizing to humans. What’s more, this farmed fish is less expensive than fresh fish, which has given rise to an economically priced seafood alternative.

“The farmed fish, they are the more stabilized; there is a stability in the price,” said John Zouras, who has worked in the Athens Central market for the last five years. He is the third generation in his family there, and is also the general secretary of the council overseeing the market. Of the wild caught fish, he said, «It’s not stable, because in one week, they have a lot of fish. The next week, they have nothing.»

A fishing history

In the Mediterranean, fish stocks have been on the decline for over a decade due to unsustainable fishing practices, such as catching fish when they are too small and before they have a chance to spawn. Limitations were put in place to protect Bluefin tuna in early 2000s, and those limitations worked well, encouraging further catch limitations on struggling fish populations.

«The fish stocks in the Mediterranean, they are overexploited,» said Dario Pinello, a fishery economist who works at Nisea Cooperative, an institute for fisheries and aquaculture economic research in Italy. «According to the biologists that conduct the official stock assessment, most of 90 percent of the fish stocks in the Mediterranean are considered overexploited,» he said.

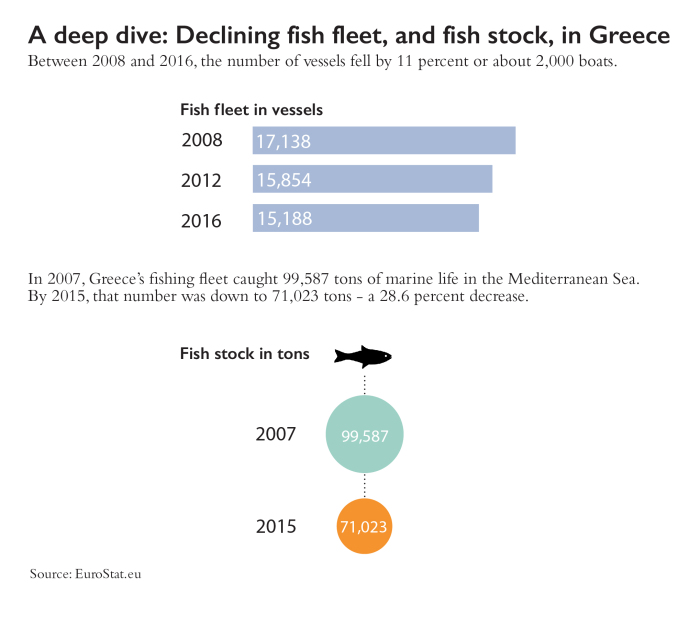

Greece boasts one of the largest fishing fleets in the Mediterranean. But the number of vessels continues to drop. Between 2008 and 2016, vessels fell by 11 percent to 15,188, according to Eurostat. That means about 2000 fewer boats.

Graphic by Suma Hussien

Those close to the industry blame regulations set forth by the Greek government in 2014 by the Common Fisheries Policies (CFP). The new policy introduces sustainable catch limits, more selective catches of a number of fish types such as mackerel and swordfish, and an obligation to dock after going out to fish to track and log catches.

«There are limitations on their fishing tools,» said Karapanagiotidis, from the University of Thessaly in Volos. «So let’s say they are using nets. [New rules dictate] how many kilometers of net they can use, and what size of the holes – the mesh size of the net.»

Regulations are designed to keep resources sustainable in an effort to protect the environment and keep ocean life healthy for human consumption. The protection of fish stocks and the marine environment is a key issue, experts say, given the threat posed by resource depletion.

«There are seasonal limitations as well,» said Karapanagiotidis. «They must follow the limitations on the areas, depending on the target species they are catching.»

The results of such restrictions are evident. In 2007, Greece’s fishing fleet caught 99,587 tons of marine life in the Mediterranean Sea, according to EuroStat.eu. By 2015, that number was down to 71,023 tons – a 28.6 percent decrease.

These dropping numbers translate directly to the wallets of fishermen, since they don’t receive any government subsidies or salaries. They can only depend on the amount of fish they sell and have to hope that number fetches more than the cost of boat upkeep and fuel.

«Less and less people are getting involved with fishing,» said Karapanagiotidis. «And this is due to the income. The income is not as good as it was in the past, due to smaller catches. The other thing is that it is a hard job for someone, so then they do not get paid as well, it is not as interesting to a young person to get involved with it.»

A country turns to fish farming

Fish is one of the staples in the Greek diet, and the most exported animal product. Of the country’s total agricultural exports, which make up 19 percent of the total, marine fish contributes 11 percent, making it the top animal product.

But Greece is now listed as the fifth largest farmed fish producer behind Spain, the United Kingdom, France and Italy, focusing primarily on finfish such as gilthead sea bream – which is a white flaky fish often served whole in Greece – and European sea bass, as well as mussels. Up to 78 percent of fish farmed in Greece was exported to 32 countries in 2015, including to Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong and China.

As a result, the number of farms in recent years has exploded. As of 2013, there were 63 fish farm companies in Greece – 336 farm sites spread around the country and 36 land-based hatcheries – according to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website. Most of these producers are small to medium-sized family businesses.

A fish seller stands at his stall in the Athens Central Market. On the left is fish from farms, being sold for 2.98 and 4.98 euro, as compared to the fish on the right from the wild at 4.50 and 5.98 euro. Photo by Suma Hussien

«Aquaculture has become the major provider of fish worldwide,» said Karapanagiotidis.

Since 2003, marine fish farming has had a larger market share than wild caught fish in Greece. And by 2013, 69 percent of total fishery products came from farming, a trend on track to continue.

In addition, marine fish farming in Greece provides 12,000 jobs, mainly in remote and isolated areas. In several cases, it is the major employer for a region. And an additional 5,000 jobs exist in the chain of distribution of products and peripheral activities.

The markets tell the story

In the early morning quiet, the Kapani market in the heart of Thessaloniki has already begun to wake before its 7:30 opening. This market is the oldest in Thessaloniki, and it stands in the same place it has since the 15th century. As the sky lightens with the rising sun, vendors deliver bags of crushed ice to stands along the alleyways for sellers to spread over their display counters. Soon, more delivery vans will arrive, bringing in the fish for the market from landing ports.

Alexandros Moustras and his comrades sit, waiting for the arrival of the van so they can begin to set up their display for the day. As they wait, the men sip coffees and trade jokes. They are not fishermen themselves, as the port of Thessaloniki is not suitable to fish due to pollution from oil and cargo ships.

«We only sell fish – buy and sell,» said Moustras, who has worked in the market for the last 12 years. «We have one guy, he works only at night, he goes to get the fish and brings them back in the morning.» The fishing ports are further up and down the coast including from Chalkidiki, which is a two-hour drive south. All fish sold in this market come from the Aegean Sea, said Demetrios Mechenione, who works in a fish stall with his father and mother. Around Greece, there are 12 major fishing ports, as well as a number of smaller localized ports on the islands.

Greece’s substantial production can be attributed to its coastline. «It has one of the longest coastlines in the world if you count the islands,» said Lara Barazi-Yeroulanos, whose father-in-law started his fish farming company, Kefalonia Fisheries, in the early 1980s on the Greek island Kefalonia. «So that provides the space to do this,» she said.

Alexandros Moustras setting up his stand in the Kapani market in Thessaloniki. Photo by Alexa LaVersa

While fish farming has provided a less expensive alternative to wild fish, it has also created competition within the marketplace. The main farmed products, sea bass and sea bream, are also two of the most overfished species, so there isn’t much competition between wild and farmed fish in that sense. But the high-quality wild-caught fish will often be overlooked in favor of either lower quality wild species, or the less expensive farmed alternatives.

«The aquaculture products do compete, but with low quality and low-priced fishes landed by the Greek fisheries,» said Pinello. «So only those species are suffering from the competition with aquaculture products.»

Competition extends into the fish farms as well. Small farms make up 30 percent of the fish farm production, according to Barazi-Yeroulanos, and there are only two companies that hold the remaining 70 percent of production, Selonda and Nireus.

«The industry has become very concentrated in the last seven years,» said Barazi-Yeroulanos, who is chief executive officer for her father’s company. «There’s just not many [small farms] left.»

As the men working in the market attempt to make a living, they need to also think of their customer’s wallets. «The products of aquaculture is something that the consumer can afford,» said Zouras. «And generally, with the financial crisis, more people choose the fish from aquaculture.»

At Kapani market in Thessaloniki, a white van finally pulls up, and the men with Moustras rise from their seats, ready to help unpack the day’s catch into separate orders. Light rain falls on the roof of the covered market as the men quietly set to work.

The first customers of the day began to trickle in. They’re browsing slowly as the fish – mackerel, sole, mullet – are laid out neatly for display. And just like that, another business day has begun here, like the thousands of days before it in this ancient Greek market, and likely the thousands of days ahead.